Here are three intertwined posts in one: a report from inside a workshop on Facebook’s Oversight Board; a follow-up on the working group on net regulation I’m part of; and a brief book report on Jeff Kosseff’s new and very good biography of Section 230, The Twenty-Six Words That Created the Internet.

Facebook’s Oversight BoardLast week, I was invited — with about 40 others from law, media, civil society, and the academe — to one of a half-dozen workshops Facebook is holding globally to grapple with the thicket of thorny questions associated with the external oversight board Mark Zuckerberg promised.

(Disclosures: I raised money for my school from Facebook. We are independent and I receive no compensation personally from any platform. The workshop was held under Chatham House rule. I declined to sign an NDA and none was then required, but details about to real case studies were off the record.)

You may judge the oversight board as you like: as an earnest attempt to bring order and due process to Facebook’s moderation; as an effort by Facebook to slough off its responsibility onto outsiders; as a PR stunt. Through the two-day workshop, the group kept trying to find an analog for Facebook’s vision of this: Is it an appeals court, a small-claims court, a policy-setting legislature, an advisory council? Facebook said the board will have final say on content moderation appeals regarding Facebook and Instagram and will advise on policy. It’s two mints in one.

The devil is the details. Who is appointed to the board and how? How diverse and by what definitions of diversity are the members of the board selected? Who brings cases to the board (Facebook? people whose content was taken down? people who complained about content? board members?)? How does the board decide what cases to hear? Does the board enforce Facebook policyor can it countermand it? How much access to data about cases and usage will the board have? How much authority will the board have to bring in experts and researchers and what access to data will they have? How does the board scale its decision-making when Facebook receives 3 million reports against content a day? How is consistency found among the decisions of three-member panels in the 40ish-member board? How can a single board in a single global company be consistent across a universe of cultural differences and sensitive to them? As is Facebook’s habit, the event was tightly scheduled with presentations and case studies and so — at least before I had to leave in day two — there was less open debate of these fascinating questions than I’d have liked.

Facebook starts with its 40 pages of community standards, updated about every two weeks, which are in essence its statutes. I recommend you look through them. They are thoughtful and detailed. For example:

A hate organization is defined as: Any association of three or more people that is organized under a name, sign or symbol and that has an ideology, statements or physical actions that attack individuals based on characteristics, including race, religious affiliation, nationality, ethnicity, gender, sex, sexual orientation, serious disease or disability.

At the workshop, we heard how a policy team sets these rules, how product teams create the tools around them, and how operations — with people in 20 offices around the world, working 24/7, in 50 languages — are trained to enforce them.

But rules — no matter how detailed — are proving insufficient to douse the fires around Facebook. Witness the case, only days after the workshop, of the manipulated Nancy Pelosi video and subsequent cries for Facebook to take it down. I was amazed that so many smart people thought it was an easy matter for Facebook to take down the video because it was false, without acknowledging the precedent that would set requiring Facebook henceforth to rule on the truth of everything everyone says on its platform — something no one should want. Facebook VP for Product Policy and Counterterrorism Monika Bickert (FYI: I interviewed her at a Facebook safety event the week before) said the company demoted the video in News Feed and added a warning to the video. But that wasn’t enough for those out for Facebook’s hide. Here’s a member of the UK Parliament (who was responsible for the Commons report on the net I criticized here):

What standard do you want? Do you wish Facebook to decide truth?

— Jeff Jarvis (@jeffjarvis) May 25, 2019

Jeff it’s already been independently certified as being fake. What Facebook are saying is that they won’t take down known sources of malicious political disinformation.

— Damian Collins (@DamianCollins) May 25, 2019

Damian, are you then going to expect them to take down any other video–or anything else–certified as fake? Certified by whom? Do you also want destruction of the evidence of this manipulation? Beware: slope slippery ahead.

— Jeff Jarvis (@jeffjarvis) May 25, 2019

So by Collins’ standard, if UK politicians in his own party claim as a matter of malicious political disinformation that the country pays £350m per week to the EU that would be freed up for the National Health Service with Brexit and that’s certified by journalists to be “willful distortion,” should Facebook be required to take that statement down? Just asking. It’s not hard to see where this notion of banning falsity goes off the rails and has a deleterious impact on freedom of expression and political discussion.

But politicians want to take bites out of Facebook’s butt. They want to blame Facebook for the ill-informed state of political debate. They want to ignore their own culpability. They want to blame technology and technology companies for what people — citizens — are doing.

Ditto media. Here’s Kara Swisher tearing off her bit of Facebook flesh regarding the Pelosi video: “Would a broadcast network air this? Never. Would a newspaper publish it? Not without serious repercussions. Would a marketing campaign like this ever pass muster? False advertising.”

Sigh. The internet is not media. Facebook is not news (only 4% of what appears there is). What you see there is not content. It is conversation. The internet and Facebook are means for the vast majority of citizenry forever locked out of media and of politics to discuss whatever they want, whether you like it or not. Those who want to control that conversation are the privileged and powerful who resent competition from new voices.

By the way, media people: Beware what you wish for when you declare that platforms are media and that they must do this or that, for your wishes could blow back on you and open the door for governments and others to demand that media also erase that which someone declares to be false.

Facebook’s oversight board is trying to mollify its critics — and forestall regulation of it — by meeting their demands to regulate content. Therein lies its weakness, I think: regulating content.

Regulating Actors, Behaviors, or ContentA week before the Facebook workshop, I attended a second meeting of a Transatlantic High Level Working Group on Content Moderation and Freedom of Expression (read: regulation), which I wrote about earlier. At the first meeting, we looked at separating treatment of undesirable content (dealt with under community standards such as Facebook’s) from illegal content (which should be the purview of government and of an internet court; details on that proposal here.)

At this second meeting, one of the brilliant members of the group (held under Chatham House, so I can’t say who) proposed a fundamental shift in how to look at efforts to regulate the internet, proposing an ABC rule separating actors from behaviors from content. (Here’s another take on the latest meeting from a participant.)

It took me time to understand this, but it became clear in our discussion that regulating content is a dangerous path. First, making content illegal is making speech illegal. As long as we have a First Amendment and a Section 230 (more on that below) in the United States, that is a fraught notion. In the UK, a Commons committee recently released an Online Harms White Paper that demonstrates just how dangerous the idea of regulating content can be. The white paper wants to require — under pain of huge financial penalty for companies and executives — that platforms exercise a duty of care to take down “threats to our way of life” that include not only illegal and harmful content (child porn, terrorism) but also legal and harmful content (including trolling [please define] and disinformation [see above]). Can’t they see that government requiring the takedown of legal content makes it illegal? Can’t they see that by not defining harmful content, they put a chill on all speech? For an excellent takedown of the report, see this post by Graham Smith, who says that what the Commons committee is impossibly vague. He writes:

‘Harm’ as such has no identifiable boundaries, at least none that would pass a legislative certainty test.

This is particularly evident in the White Paper’s discussion of Disinformation. In the context of anti-vaccination the White Paper notes that “Inaccurate information, regardless of intent, can be harmful”.

Having equated inaccuracy with harm, the White Paper contradictorily claims that the regulator and its online intermediary proxies can protect users from harm without policing truth or accuracy…

See: This is the problem when you try to identify, regulate, and eliminate bad content. Smith concludes: “This is a mechanism for control of individual speech such as would not be contemplated offline and is fundamentally unsuited to what individuals do and say online.” Nevermind the common analogy to regulation of broadcast. Would we ever suffer such talk about regulating the contents of bookstores or newspapers or — more to the point — conversations in the corner bar?

What becomes clear is that these regulatory methods — private (at Facebook) and public (in the UK and across Europe) — are aimed not at content but ultimately at behavior, only they don’t say so. It is nearly impossible to judge content in isolation. For example, my liberal world is screaming about the slow-Pelosi video. But then what about this video from three years ago?

What makes one abhorrent and one funny? The eye of the beholder? The intent of the creator? Both. Thus content can’t be judged on its own. Context matters. Motive matters. But who is to judge intent and impact and how?

The problem is that politicians and media do not like certain behavior by certain citizens. They cannot figure out how to regulate it at scale (and would prefer not to make the often unpopular decisions required), so they assign the task to intermediaries — platforms. Pols also cannot figure out how to define the bad behavior they want to forbid, so they decide instead to turn an act into a thing — content — and outlaw that under vague rules they expect intermediaries to enforce … or else.

The intermediaries, in turn, cannot figure out how to take this task on at scale and without risk. In an excellent Harvard Law Review paper called The New Governors: The People, Rules, and Processes Governing Online Speech, legal scholar Kate Klonick explains that the platforms began by setting standards. Facebook’s early content moderation guide was a page long, “so it was things like Hitler and naked people,” says early Facebook community exec Dave Willner. Charlotte Willner, who worked in customer service then (they’re now married), said moderators were told “if it makes you feel bad in your gut, then go ahead and take it down.” But standards — or statements of values— don’t scale as they are “often vague and open ended” and can be “subject to arbitrary and/or prejudiced enforcement.” And algos don’t grok values. So the platforms had to shift from standards to rules. “Rules are comparatively cheap and easy to enforce,” says Klonick, “but they can be over- and underinclusive and, thus, can lead to unfair results. Rules permit little discretion and in this sense limit the whims of decisionmakers, but they also can contain gaps and conflicts, creating complexity and litigation.” That’s where we are today. Thus Facebook’s systems, algorithmic and human, followed its rules when they came across the historic photo of a child in a napalm attack. Child? Check. Naked? Check. At risk? Check. Take it down. The rules and the systems of enforcement could not cope with the idea that what was indecent in that photo was the napalm.

Thus the platforms found their rule-led moderators and especially their algorithms needed nuance. Thus the proposal for Facebook’s Oversight Board. Thus the proposal for internet courts. These are attempts to bring human judgment back into the process. They attempt to bring back the context that standards provide over rules. As they do their work, I predict these boards and courts will inevitably shift from debating the acceptability of speech to trying to discern the intent of speakers and the impact on listeners. They won’t be regulating a thing: content. They will be regulating the behavior of actors: us.

There are additional weaknesses to the rules-based, content-based approach. One is that community standards are rarely set by the communities themselves; they are imposed on communities by companies. How could it be otherwise? I remember long ago that Zuckerberg proposed creating a crowdsourced constitution for Facebook but that quickly proved unwieldy. I still wonder whether there are creative ways to get intentional and explicit judgments from communities as to what is and isn’t acceptable for them — if not in a global service, then user-by-user or community-by-community. A second weakness of the community standards approach is that these rules bind users but not platforms. I argued in a prior post that platforms should create two-way covenants with their communities, making assurances of what the company will deliver so it can be held accountable.

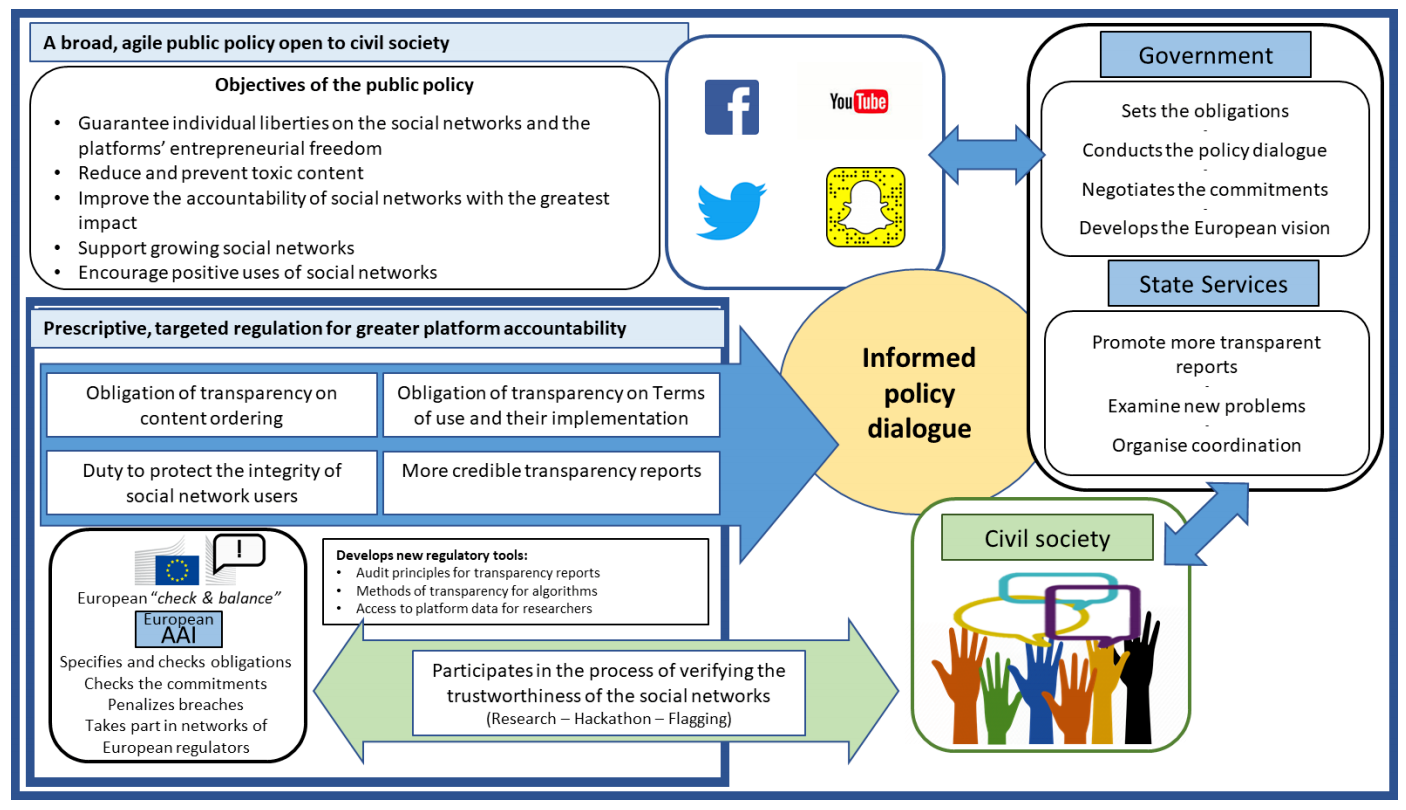

Earlier this month, the French government proposed an admirably sensible scheme for regulation that tries to address a few of those issues. French authorities spent months embedded in Facebook in a role-playing exercise to understand how they could regulate the platform. I met a regulator in charge of this effort and was impressed with his nuanced, sensible, smart, and calm sense of the task. The proposal does not want to regulate content directly — as the Germans do with their hate speech law, called NetzDG, and as the Brits propose to do going after online harms.

Instead, the French want to hold the platforms accountable for enforcing the standards and promises they set: say what you do, do what you say. That enables each platform and community to have its own appropriate standards (Reddit ain’t Facebook). It motivates platforms to work with their users to set standards. It enables government and civil society to consult on how standards are set. It requires platforms to provide data about their performance and impact to regulators as well as researchers. And it holds companies accountable for whether they do what they say they will do. It enables the platforms to still self-regulate and brings credibility through transparency to those efforts. Though simpler than other schemes, this is still complex, as the world’s most complicated PowerPoint slide illustrates:

I disagree with some of what the French argue. They call the platforms media (see my argument above). They also want to regulate only the three to five largest social platforms — Facebook, YouTube, Twitter— because they have greater impact (and because that’s easier for the regulators). Except as soon as certain groups are shooed out of those big platforms, they will dig into small platforms, feeling marginalized and perhaps radicalized, and do their damage from there. The French think some of those sites are toxic and can’t be regulated.

All of these efforts — Facebook’s oversight board, the French regulator, any proposed internet court — need to be undertaken with a clear understanding of the complexity, size, and speed of the task. I do not buy cynical arguments that social platforms want terrorism and hate speech kept up because they make money on it; bull. In Facebook’s workshop and in discussions with people at various of the platforms, I’ve gained respect for the difficulty of their work and the sincerity of their efforts. I recommend Klonick’s paper as she attempts to start with an understanding of what these companies do, arguing that

platforms have created a voluntary system of self-regulation because they are economically motivated to create a hospitable environment for their users in order to incentivize engagement. This regulation involves both reflecting the norms of their users around speech as well as keeping as much speech as possible. Online platforms also self-regulate for reasons of social and corporate responsibility, which in turn reflect free speech norms.

She quotes Lawrence Lessig predicting that a “code of cyberspace, defining the freedoms and controls of cyberspace, will be built. About that there can be no doubt. But by whom, and with what values? That is the only choice we have left to make.”

And we’re not done making it. I think we will end up with a many-tiered approach, including:

- Community standards that govern matters of acceptable and unacceptable behavior. I hope they are made with more community input.

- Platform covenants that make warranties to users, the public, and government about what they will endeavor to deliver in a safe and hospitable environment, protecting users’ human rights.

- Algorithmic means of identifying potentially violating behavior at scale.

- Human appeals that operate like small claims courts.

- High-level oversight boards that rule and advise on policy.

- Regulators that hold companies accountable for the guarantees they make.

- National internet courts that rule on questions of legality in takedowns in public, with due process. Companies should not be forced to judge legality.

- Legacy courts to deal with matters of illegal behavior. Note that platforms often judge a complaint first against their terms of service and issue a takedown before reaching questions about illegality, meaning that the miscreants who engage in that illegal behavior are not reported to authorities. I expect that governments will complain platforms aren’t doing enough of their policing — and that platforms will complain that’s government’s job.

Numbers 1–5 occur on the private, company side; the rest must be the work of government. Klonick calls the platforms “the New Governors,” explaining that

online speech platforms sit between the state and speakers and publishers. They have the role of empowering both individual speakers and publishers … and their transnational private infrastructure tempers the power of the state to censor. These New Governors have profoundly equalized access to speech publication, centralized decentralized communities, opened vast new resources of communal knowledge, and created infinite ways to spread culture. Digital speech has created a global democratic culture, and the New Governors are the architects of the governance structure that runs it.

What we are seeking is a structure of checks and balances. We need to protect the human rights of citizens to speak and to be shielded from such behaviors as harassment, threat, and malign manipulation (whether by political or economic actors). We need to govern the power of the New Governors. We also need to protect the platforms from government censorship and legal harassment. That’s why we in America have Section 230.

Section 230 and ‘The Twenty-Six Words that Created the Internet’We are having this debate at all because we have the “online speech platforms,” as Klonick calls them — and we have those platforms thanks to the protection given to technology companies as well as others (including old-fashioned publishers that go online) by Section 230, a law written by Oregon Sen. Ron Wyden (D) and former California Rep. Chris Cox (R) and passed in 1996 telecommunications reform. Jeff Kosseff wrote an excellent biography of the law that pays tribute to these 26 words in it:

No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.

Those words give online companies safe harbor from legal liability for what other people say on their sites and services. Without that protection, online site operators would have been motivated to cut off discussion and creativity by the public. Without 230, I doubt we would have Facebook, Twitter, Wikipedia, YouTube, Reddit, news comment sections, blog platforms, even blog comments. “The internet,” Kosseff writes, “would be little more than an electronic version of a traditional newspaper or TV station, with all the words, pictures, and videos provided by a company and little interaction among users.” Media might wish for that. I don’t.

In Wyden’s view, the 26 words give online companies not only this shield but also a sword: the power and freedom to moderate conversation on their sites and platforms. Before Section 230, a Prodigy case held that if an online proprietor moderated conversation and failed to catch something bad, the operator would be more liable than if it had not moderated at all. Section 230 reversed that so that online companies would be free to moderate without moderating perfectly — a necessity to encourage moderation at scale. Lately, Wyden has pushed the platforms to use their sword more.

In the debate on 230 on the House floor, Cox said his law “will establish as the policy of the United States that we do not wish to have content regulation by the Federal Government of what is on the internet, that we do not wish to have a Federal Computer Commission with an army of bureaucrats regulating the internet….”

In his book, Kosseff takes us through the prehistory of 230 and why it was necessary, then the case law of how 230 has been tested again and again and, so far, survived.

But Section 230 is at risk from many quarters. From the far right, we hear Trump and his cultists whine that they are being discriminated against because their hateful disinformation (see: Infowars) is being taken down. From the left, we see liberals and media gang up on the platforms in a fit of what I see as moral panic to blame them for every ill in the public conversation (ignoring politicians’ and media’s fault). Thus they call for regulating and breaking up technology companies. In Europe, countries are holding the platforms — and their executives and potentially even their technologists — liable for what the public does through their technology. In other nations — China, Iran, Russia — governments are directly controlling the public conversation.

So Section 230 stands alone. It has suffered one slice in the form of the FOSTA/SESTA ban on online sex trafficking. In a visit to the Senate with the regulation working group I wrote about above, I heard a staffer warn that there could be further carve-outs regarding opioids, bullying, political extremism, and more. Meanwhile, the platforms themselves didn’t have the guts to testify in defense of 230 and against FOSTA/SESTA (who wants to seem to be on the other side of banning sex trafficking?). If these companies will not defend the internet, who will? No, Facebook and Google are not the internet. But what you do to them, you do to the net.

I worry for the future of the net and thus of the public conversation it enables. That is why I take so seriously the issues I outline above. If Section 230 is crippled; if the UK succeeds in demanding that Facebook ban undefined harmful but legal content; if Europe’s right to be forgotten expands; if France and Singapore lead to the spread of “fake news” laws that require platforms to adjudicate truth; if the authoritarian net of China and Iran continues to spread to Russia, Turkey, Hungary, the Philippines, and beyond; if …

If protections of the public conversation on the net are killed, then the public conversation will suffer and voices who could never be heard in big, old media and in big, old, top-down institutions like politics will be silenced again, which is precisely what those who used to control the conversation want. We’re in early days, friends. After five centuries of the Gutenberg era, society is just starting to relearn how to hold a conversation with itself. We need time, through fits and starts, good times and bad, to figure that out. We need our freedom protected.

Without online speech platforms and their protection and freedom, I do not think we would have had #metoo or #blacklivesmatter or #livingwhileblack. Just to see one example of what hashtags as platforms have enabled, please watch this brilliant talk by Baratunde Thurston and worry about what we could be missing.

None of this is simple and so I distrust all the politicians and columnists who think they have simple solutions: Just make Facebook kill this or Twitter that or make them pay or break them up. That’s simplistic, naive, dangerous, and destructive. This is hard. Democracy is hard.

The post Regulating the net is regulating us appeared first on BuzzMachine.